Samuel Alfred Warner on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Alfred Warner (c.1793–1853) was an English inventor of naval weapons, now considered a

A further demonstration in the

A further demonstration in the

charlatan

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through false pretenses, pretense or deception. Synonyms for ''charlatan ...

.

Life

Warner was born atHeathfield, East Sussex

Heathfield is a market town in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. The town had a population of 7,732 in 2011. With neighbouring Waldron, it forms the civil parish of the Heathfield and Waldron, which had a population of 11,913 in 2 ...

, son of William Warner who was a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, Shipbuilding, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. ...

and reputed smuggler of Faversham

Faversham is a market town in Kent, England, from London and from Canterbury, next to the Swale, a strip of sea separating mainland Kent from the Isle of Sheppey in the Thames Estuary. It is close to the A2, which follows an ancient British t ...

. He knew a London chemist called Garrald, and was working with him in 1819 on an explosive. He took service with Pedro I of Brazil

Don (honorific), Dom Pedro I (English: Peter I; 12 October 1798 – 24 September 1834), nicknamed "the Liberator", was the founder and List of monarchs of Brazil, first ruler of the Empire of Brazil. As King Dom Pedro IV, he List of ...

in Portugal, and on his return to England found some support from William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

for his claims to have secret weapons.

The King appointed Admiral Richard Goodwin Keats

Admiral Sir Richard Goodwin Keats (16 January 1757 – 5 April 1834) was a British naval officer who fought throughout the American Revolution, French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic War. He retired in 1812 due to ill health and was made Comm ...

, then Governor of the Royal Hospital Greenwich to investigate. Then admiral Sir Thomas Hardy was called in to assist. Warner died in obscure circumstances in the early days of December 1853, and was buried in Brompton cemetery

Brompton Cemetery (originally the West of London and Westminster Cemetery) is a London cemetery, managed by The Royal Parks, in West Brompton in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It is one of the Magnificent Seven cemeteries. Estab ...

, west London, on the 10th. He left a widow and seven children.

Claimed inventions

From 1830 to the date of his death Warner pressed claims for two inventions. These were the "invisible shell" (reconstructed as a type of high explosive underwater mine), and the "long range", possibly a balloon fitted to drop the "invisible shells" automatically: it emerged eventually that Warner had secretly set up an unsuccessful trial with Charles Green and an unmanned balloon. A demonstration of 1841 on a lake inEssex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

saw a boat blown up, watched by a group including Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

.

Small committees were appointed to examine and experiment on these inventions, but Warner refused to show or in any way explain his secrets till he was assured of the payment of £200,000 for each. In 1842 a committee of Sir Thomas Byam Martin

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Thomas Byam Martin, (25 July 1773 – 25 October 1854) was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of fifth-rate HMS ''Fisgard'' he took part in a duel with the French ship ''Immortalité'' and captured her at the Battl ...

and Sir Howard Douglas

General Sir Howard Douglas, 3rd Baronet, (23 January 1776 – 9 November 1861) was a British Army officer born in Gosport, England, the younger son of Admiral Sir Charles Douglas, and a descendant of the Earls of Morton. He was an English ...

questioned Warner. He stated that his father was William Warner, who in 1812 had owned and commanded the ''Nautilus'', hired by the government for covert work in espionage; that he himself had served with his father in the ''Nautilus'', and had, towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, by means of his invention, destroyed two of the enemy's privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s. There was no verification and the account was marred by anachronism

An anachronism (from the Ancient Greek, Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronology, chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time per ...

s.

At the same period Warner's claims were assessed by Lieutenant-Colonel Chalmer of the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

, and Commander James Crawford Caffin.

A further demonstration in the

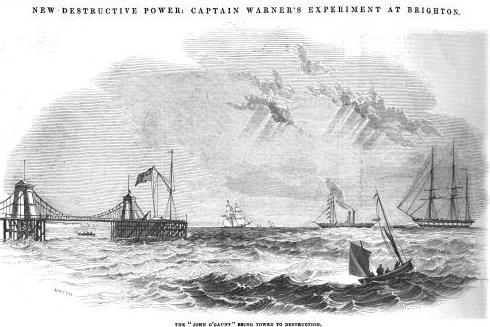

A further demonstration in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

off Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

in 1844 showed a target vessel being towed at sea detonated at a signal. It was well attended, but left unresolved the value of what had been seen.

Warner claimed that Keats and Hardy had authored a report in support of the invention, and presented a purported copy. It was noted in parliament that no other copy was to be found. Keats and Hardy were long since dead, and it was noted it was singular they should die, and no copy be found, it being notorious they were both men of business and not likely to have lost their papers. It was concluded no such report existed.

The supposed inventions were displayed in the West End Gallery at the great Exhibition of 1851, still claiming the support of Keats and Hardy, but it progressed no further.Hannah. p. 275. In 1852 the matter was again brought up in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, on 14 May, and a committee was appointed to inquire into it. A week later, on 21 May, the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

intervened, pointing out that the inquiry was one of a scientific nature, and that it had been entrusted to the Ordnance Department. With this the matter appears to have been dropped. The committee never reported.

See also

*Harry Grindell Matthews

Harry Grindell Matthews (17 March 1880 – 11 September 1941) was an English inventor who claimed to have invented a death ray in the 1920s.

Earlier life and inventions

Harry Grindell Matthews was born on 17 March 1880 in Winterbourne, Glo ...

Notes

Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Warner, Samuel Alfred 1793 births 1853 deaths English inventors English fraudsters People from Heathfield, East Sussex 19th-century English businesspeople Burials at Brompton Cemetery